METHODOLOGY: THE POSSIBILITIES AND LIMITATIONS OF 'INFERENCE': TITLES AS KEYS.

The scarcity of statements by the artist, about his work [limited to six aphorisms published in the catalogue of his Arnolfini solo show, in 1966], makes us dependent on TITLES of works in exhibition CATALOGUES:

1. to figure out the extent of Taylor's oeuvre,

2. to infer his artistic concerns, references, and subject-matter, and

3. to consider how they manifested themselves in forms and motifs, across and between different media.

This, to say the least, calls for creative speculation; at the risk of generating fictions.

Exhibition catalogues are invaluable, for they identify, by their TITLES, 30 or so works that were exhibited at the Drian Gallery in 1958, in two exhibitions [only two works recurring in both exhibitions: 'May-bug' and 'Crucifixion'].

[see reference in St Ives Times and E cho]

This and other catalogues suggests that 1957-58 was a very productive time in Taylor's artistic life as well as 1963-65.

The catalogue of his Arnolfini solo exhibition, in 1965, confirm that the following years were productive, too; but, all in all, it seems that Taylor produced a small body of work. A fact that may have contributed to his disappearance, alongside his lack of social ambition.

WHAT IS IN A TITLE?

REFERENCE IN TAYLOR'S WORKS

Working with

1. titles of works listed in catalogues [under a hundred],

2. actual works that I have located and/or collected,

3. unlabelled photographs of works which I have not, in most cases, been able to trace, yet,

4. the photograph of one work known to be in a private collection,

invites us to make creative extrapolations that may throw light into Taylor's interests and preoccupations and about the subject matter of his work.

This is important to situate him stylistically and conceptually among his contemporaries; in St Ives and elsewhere.

The exhibition I have in mind will emphatically list all the titles (in vinyl text) — as interpretive clues — and invite visitors to try and match the works in the exhibitions with the titles.

The exhibition I have in mind will emphatically list all the titles (in vinyl text) — as interpretive clues — and invite visitors to try and match the works in the exhibitions with the titles.

The photographs of works that have not been located [and are only known through these photographs] can — especially when showing plaster maquettes for bronzes that may never have been cast — help us catch a glimpse of the formal development of themes and motifs, and his uses of media [welded steel and bronze], and compare them with the works that we do have [see list in right hand column >]

The TITLES of the works Taylor exhibited at The Drian Gallery in 1958, fall under two categories — 'Drawings' and 'Sculpture' — and refer to a wide range of realities.

At one end of the scale, they evoke a COSMIC DIMENSION; at the other, they denote ORGANIC LIFE and ABSTRACT GEOMETRIC FORMS.

1. Cosmic dimension: Firmament, Planets, Nebulae (57), Satellite,

2. Organic life forms (real or imaginary): Sea horse, Sea form, May-bug.

3. In between, one drawing titled 'Landscape', and a painting 'Ore stream', reference the Cornish landscape, more or less obliquely.

4. A fourth group (sculptures) has mythological or religious resonances: Oracle, Crucifixion.

5. Among the 'drawings', some were clearly intended as studies for sculptures: 'Drawing for wire construction', 'Drawing for Sculpture, August 1957'.

In 1957, the Arts Council toured a second exhibition of works by members of the Penwith Society [the 1st in 1954, the third in 1960], in which Taylor exhibited a 'Drawing for sculpture' in Indian ink [size: 19 1/2 x 12 in], evidence that he used drawing as a medium for developing ideas for sculptures, but in a less literal way than sculptors like Henry Moore, whose drawings visualized or approximated their actual sculptures (an approach that Moore departed from later, realizing that the drawings were making the sculptures obsolete).

As we can see from two of these drawings [one actual drawing and a photograph of one from the 1958 Drian solo exhibition catalogue], Taylor's drawing are not literal notations of sculptural forms, but more like notations of GESTURES representing lines of ENERGY IN MOVEMENT.

Closer, in spirit, to his painting 'Ore Stream', the drawing is more abstract (or more ambiguously referential).

Bergson's book 'Creative Evolution' seems particularly relevant, here, for it helps us situate Taylor's practice, in particular his transmutation of human impulses and 'experiences' into concrete 'form' and 'works', outside the polarity of figuration/ abstraction.

The simplistic dualism artists and critics resorted to, and the aesthetic assumptions that went with it, is problematic and unhelpful to define a practice that seemed concerned with exploring the transformation and transmutation of life energies.

Taylor may have developed a secular form of VITALISM, perhaps after reading Bergson, but no necessaily so; which enabled him to create LIFE FORMS — whether human, animal or hybrid — that were not literal, but metaphoric expressions of LIFE in its incontrovertible reality.

6. Some titles just consist of a date: December 30th 1957, Drawing January 1957; thus concealing the realities and the 'problématiques' that inspired them.

Six out of the eight works Taylor exhibited in the Drian Gallery group show only bear a date as their title [The two exceptions were the Kafkaesque 'May-bug' and 'Crucifixion'].

7. Some two dimensional works refer to the color used: Blue-black drawing, Blue vertical (oil), Green Drawing 1957.

8. The title of one sculpture [labelled 'in collection of Mrs Sybil Hanson'] refers to a purely formal /geometric property: Convexity.

This way of titling works, which emphasized FORM, MATERIAL and MOVEMENT rather than what we may call their 'object-matter' was in-keeping with a practice, widespread among St Ives sculptors, and indicated a tendency towards 'formal abstraction'.

Thus 'Copper Forms', 'Copper and Slate', 'Plaster Abstract Nº1' (Denis Mitchell); 'Steel Yellow 5, 1957', 'Canterlevered White, 1958' (Brian Wall); 'Torsion (oak)', 'Counterthrust (Portugal Laurel)' (Roger Leigh).

Among the other works — 'Ascending form' may suggests an organic-spiritual (Vitalist?) reference whilst 'War Head' denotes a political one.

However suggestive these titles may be, they only provide a loose basis for creative speculation.

WHAT TITLES REVEAL

1. COSMIC DIMENSION

Generic references to SPACE (that the first space expeditions had started to explore), to the infinite dimension of the universe, and to the existence of forces beyond our grasp and our control. These may have expressed Taylor's metaphysical concerns and his anxieties and those of his contemporaries.

Although no evidence confirms in which direction to hypothesize, various statements by contemporary artists situate their practices — however stylistically different — as oscillating between local and cosmic dimensions.

[give examples]

'SATELLITE':

With 'satellite', the reference is more explicit.

In 1958, the word 'satellite' had strong associations.

In 4th October 1957 the Soviet Union had successfully launched and put onto orbit Sputnik 1, that had completed 1350 orbits in 22 days; beating the American into what was to become the 'Space Race':

On January 31, 1958, the Americans launched Explorer 1. Then followed a series of expeditions that culminated with the launch of the first man in space, Gagarin, on April 12, 1961.

Titles alone do not enable us to say if and how these international events informed Taylor's works. Without a work or a photograph of the work (only a title in a catalogue), we can only surmise that it caught Taylor's imagination; showing that the excentered position of st Ives did not isolate artists from contemporary world events.

WAR HEAD

The 'SPACE RACE' launched by the launch of Sputnick 1 into space, and the fact that, on May 15 1957, the first British H Bomb was tested at Christmas island, may or may not bear directly upon the 'War head'.

On 30th May 1958, The St Ives Times and Echo published an advert for a feature about Hiroshima:

Let's note, here, that the title War Head extends Taylor's references beyond organic life forms and points in the direction of disturbing contemporary political realities: the Cold War, the Nuclear Arms Race, the threat of a IIIrd World War…) that were in every responsible person's mind.

Having served in the the army between 1941 and 1946, the term 'War head' must have connoted precise realities, that are surprisingly absent from art historical discussions of St Ives art and more generally of Modernism; which tend to focus on form, styles and aesthetics.

In this context, and with reference to similarly titled works by other artist, the works ORACLE and CRUCIFIXION suggests that Taylor's preoccupation extended beyond formalist abstractions from nature, but involved a human awareness of and a serious concern about what was happening in the world, on a planetary scale.

These concerns expressed — or at least show affinities with — two (now not fashionable) philosophical tendencies: 'Vitalism' and 'Humanism'.

|

| 'War Head'?, Photograph mounted on board (Inscribed on the back '25 1/4" high. Welded steel'). This work was taken to France and can be seen in a photograph taken at his home at Mas Fourtou. |

ORACLE & CRUCIFIXION

The absence of any evidence linking Oracle and Crucifixion with existing works or photographs of works by Taylor, leaves us with no basis to speculate. Although we know that several artist made works that refer to the'Crucifixion', using the theme theologically or metaphorically and humanistically to express the suffering of human kind following a disaster: war, an accident (Peter Lanyon: St Just Mining tragedy), or the threat of a nuclear holocaust.

2. ORGANIC LIFE FORMS

Sculptures whose titles suggest organic life forms — Sea horse, Sea form, May-bug — refer to both real or imaginary (hybrid) creatures.

The signed bronze, below, may be Sea form or Sea horse, exhibited at his solo show at Drian (1958):

By contrast May-Bug:

shows an insect-like shell.

Whether in welded steel or in bronze this group represents Taylor's dominant subject-matter; although in some cases the reference is tenuous.

The bronze, below, cast from a welded steel figure (and preserving the marks of welding) reduces the human form to its simplest totemic expression:

This work — Warrior II, 1964 ? — may have been a maquette for a larger work. I features in a photograph taken in the living room at Mas Fourtou, alongside 'Sentinel', proof of Taylor's attachment to them.

Three triangles protruding from a vertical axis, confer upon the figure a dynamic equilibrium; like three cardinal points that connect the figure with the surrounding space.

The great economy of means and formal simplicity in the depiction of the human figure, contrast with Reg Butler' insect-like, linear Woman (1949) [which he described as an experiment in 'knitting in steel'] and with the more static, fleshy totem quality of Idol 2 by William Turbull (1956) and Cyclops (1957) by Paolozzi. Simpler and more hieratic than Giacometti's figures:

Taylor produced a powerful icon which presents affinities with Chadwick in its surface texture and winged figures.

Two casts have been found of this work.

A small work in welded steel represents what looks like a figure entangled in a web of appendages or external organs (?) — half human half machine ? — that gives it either a surreal, science fiction touch or a tribal ritual (fetish) quality:

This and the one above embody the 'linear, cursive quality' noted by Herbert Read in his essay for the 1952 Venice Biennale and bears some affinity with Symbol for Man IX by Geofrey Clarke:

|

| Geofrey Clarke , Symbol for Man IX (1951): |

Another piece by Taylor, in welded steel, evokes a hybrid life form, straight out of the world of Jeronimus Bosch, reminiscent of González and of Giacometti (in his Surrealist period) as well as of the work of the African 'forgerons' that Henry Moore had admired in the Musée de l'Homme, in Paris, and that Geoffrey Clarke emulated in Horse and Rider and Effigy (both 1951):

|

| B. Taylor, Title unknown, c. 1956-7. Features in a photograph taken at the Taylor home at Bosporthennis in 1958. |

What is striking, here, is the dynamic equilibrium this work exhudes, and its monumentality, in spite of its small size.

Implicit in this 'abstract' construction one senses the presence of a figure (a hybrid between plant and animal) caught in a process of growth and metamorphosis.

Looking closely at the way it is assembled:

Taylor deliberately built the process of decay into his work by placing sculptures outside, exposing them to the elements and seeing them transform and revert to a mineral state, completing a life cycle…

Compared with the abstract geometric steel constructions of Brian Wall, and the carved forms of Roger Leigh and Denis Mitchell exhibited at the Drian Gallery, in 1958, Taylor's works display and emphasize the process of their own making over 'object-matter'; and, in their emphasis on line and planes over mass, invite to be read as a three-dimensional drawings in space.

By emphasizing the marks/signs/traces of their own making, Taylor's works, unlike those of other St Ives sculptors, who reduced the materiality of the wood or stone they carved to the grain (visible through a highly polished surface or a tint), Taylor established a personal direction which earned him to be described as 'one of the earliest serious artists to work in this medium' (welded steel) [p.12].

A visitor to his 1958 Drian solo exhibition penciled his response to'May-bug' in the catalogue: 'sheet metal torn apart by oxy-acet. cutter. spiky shapes. Cf. Adams or Chadwick'.

The visitor was ? who became director of the Courtauld Galleries.

TOWARDS ALLEGORY

This process of abstracting motifs from nature as a basis for developping new sculptural forms led Taylor to produce allegorical forms in which human and mechanical elements are fused and hybridized.

This is evident in'Sentinel' [exhibited at Drian (cat. nº6) in 1958], in which a hybrid figure stands holding a spiked shield (or 'buckler'), weapon/symbol of resistance:

This work is radically different from Henry Moore's Warrior with Shield (1953-54), in which a seated human figure holding a shield is represented with torso, head, arms and legs; though, like in a archaeological find, parts of its limbs are missing. 'Perhaps the result of my visit to Athens and other parts of Greece in 1951', commented Moore; adding, as Taylor may have, too, 'The figure may be emotionally connected (as one critic has suggested) with one's feelings and thoughts about England during the crucial and early part of the last war' (1955).

Taylor would have been more definite than Moore about the impact of the war.

His references were probably the work of the new sculptors whose work had been showcased by Herbert Read at the Venice Biennale, in 1952, framed by the sensational slogan of ' the geometry of fear' .

Compared with'Sentinel' (1956), by David Smith, a formal assemblage (inspired by Gonzales) of welded steel elements balanced along a vertical axis:

Taylor's piece retains a stronger reference to the human body as an active agent of resistance.

The stylistic/aesthetic difference between Smith's more formal, architectural/'abstract' construction and Taylor's anthropomorphic allegorical construction — clearly showing a 'structure of resistance' — is not just a question of form (abstract vs figurative), but essentially a matter of concerns and content.

The seductiveness of Smith's 'abstract' composition, more remote from its human referent than the works of Gonzales that inspired it, does not warrant placing Taylor's Sentinel into a lower aesthetic position; but require seeing and evaluating it in terms of its own parameters and artistic-ethical concerns.

To suggest that the former is better than the other, as official art history has decided, amounts to rating formalism as superior to humanism; an opinion that is open to debate, since new art forms — as Picasso emphasized — do not not make previous works obsolete, but merely change the relations between new and old works; enriching their relations and our experience of them.

In this metal relief' from 1965, successively titled 'Metal relief', 'Relief with shield and, finally, 'Buckler' (a small hand-held shield with a spike in its center):

one of the last documented piece made by Taylor in England that I have been able to identify. A photograph describes it as 'Metal Relief' (37" high 24 1/8" wide. 1965. The back of the sculpture, however, is inscribed in French, with the address at Mas Fourtou.

|

A reappraisal of Taylor's works, today, needs to address the work not in terms of the simplistic dualism figuration . abstraction (accepting the assumptions that the new abstraction represented a progress that made figurative works obsolete), but in more sophisticated critical terms that focus on the modes of reference developed by Taylor and his contemporaries, and their effects on viewers.

What we need, beyond simplistic art historical formulas grounded in ideological preconceptions, is more sophisticated intellectual tools to make these works intelligible.

My intention, here, is not to promote Taylor as an instigator of revolutionary artistic practices, but, more modestly, to present his works in terms of the 'problématiques' and methodologies he developed; as can be inferred them from the remaining evidence, and to highlight certain experiments that broke new grounds; like his photomontage discussed at the beginning.

What is only a motif in 'Sentinel' has been amplified and become the main element in Buckler.

The absence of reference to the human figure (it is only implied), subsumed here by a symbol of resistance, and the piercing of the shield from within, confers upon the work a symbolic value presented in the ambuguous language of ALLEGORY…

FROM ORGANIC FORMS TO GEOMETRIC ABSTRACTION

In this 25" untitled Wall relief two raised lines (one perfectly vertical, the other very slightly curved) run in close parallel towards each other, with some overlap, on an narrow strip of steel; with six squares and rectangles hovering over their meeting point. Unlike in previous works, the interaction between the lines, the flat plane and the floating geometric elements produces a dynamic equilibrium, free from any direct references to nature:

listed as in a private collection:

This may be another version on the same theme.

In its juxtapposition of flat planes, the composition recalls some early Cubist compositions by Braque and Picasso, and later works by Mondrian. It also evokes the first wave of constructivist artists who emulated Nicholson.

Formally, however, it seems closer to the work of …

BRONZES

Deploring that art schools emphasized modelling at the expense of carving, Hepworth adopted and promoted direct carving. Moore used both methods.

Taylor, by contrast, used the additive process both in his welded steel and in his bronzes pieces, capitalizing, in his bronzes, on his experience with ceramics.

His treatment of bronze situates him in the tradition of Rodin, Richier, Lipchitz, Gonzales and Giacometti.

The photograph below shows two sides of two different casts (alumium and bronze) of the 'same' figure.

The contrast is striking. As we turn each cast around, the figures undergo a radical metamorphosis ; taking on a different (Jekyll-Hyde) identity.

Whereas one side it evokes a Classical mythological figure — Ariadne-like — the other echoes the monsters in the garden of Bomarzo (Italy), with echoes of Rodin, LIpchitz and Richier :

A failed cast for an intricate 'abstract' construction reveals a never seen side the creative process — where the materiality and physical interaction between mould and metal short-circuits the artistic idea. It offers the spectacle of a work 'in ruin'; something normally only seen by the artist. The fact that Taylor kept it and took it to France, when he moved there suggests that the accident held something meaningful and of interest to him.

The inclusion of this 'ruin' into the exhibition is intended to make tangible the chain of processes along which form flows before it can reach us and become a work. It also illustrates Taylor's acceptance of the accident as a manifestation of life itself.

The patinated bronze (below), by Lipchitz, retains a clear link with the world of organic life forms; emphasized by the stance of the creature and the animated surface of the metal, radically different from the highly polished and more geometric works of Hepworth, Roger Leigh, Denis Mitchell and other St Ives sculptors.

Formally, Taylor's 'Sea Horse' or 'Sea Form' echoes the texture of some bronzes from the early 50s, by Henry Moore; in which the surface still carries the traces of carving, scratching and scouring. It also recalls the organic fluidity of Degas, Matisse and Lipchitz in their treatment of form:

|

| Lipchitz, Untitled, Sudy for Pastoral. c. 1935 |

An aluminium cast illustrates a preliminary stage in the development of the work.

In the piece below, the reference to life forms is more generic and ambiguous.

In the piece below, the reference to life forms is more generic and ambiguous.

The sculpture may evoke a 'life form' found on the sea bed, at great depths; devoid of sensory organs as we know them, but harbouring life, nevertheless: suggestive of an alien life forms or a 'volcanic bomb'.

Here the focus on volume, form, weight, and the absence of movement incapsulates Herbert Read's remarks that the new sculpture was concerned with 'transformation' and 'transmutation'.

Meteorite, cire perdue bronze, 1961.

Several photographs of sculptures, including plaster models (works only known to us through photographs), show that Taylor's forms became more generic and 'abstract', but retained a reference to the organic world. In these works, forms become ambiguous and textures more varied and complex; as is evidenced in the work below:

in which it is not clear whether we are looking an an organic form that has been petrified or at an accident of nature, like some rocky promontory suggestive of 'heads', 'eagles', etc. or the rabbit-duck paradox.

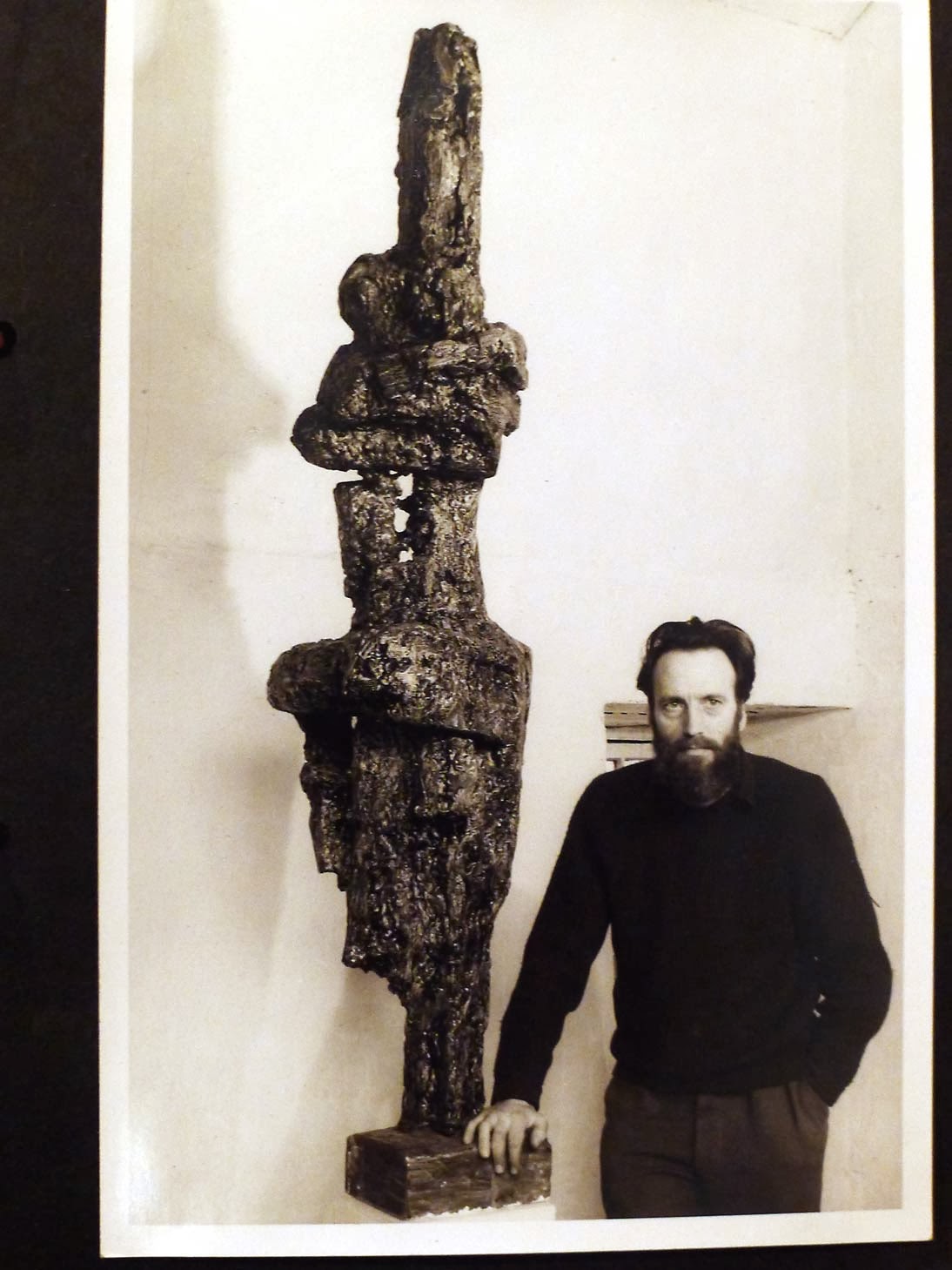

The photograph below (c. 1957-8) shows Taylor standing next to a larger work in patinated plaster (?) that may be 'Ascending forms':

BRUCE TAYLOR (1921-2004) |

Although such work could have been cast locally (at a foundry in St Just), the cost would have been high for a young artist and for a work that was not a commission; which may explain why the bronzes we have are small works, suitable for display in the home. This is probably a work in plaster, photographed in his studio at Fore Street, and the subject of a claim for insurance compensation, resulting from damage during transport to an exhibition.

Taylor's largest works [King and Queen (79 x 60), Eclipse II (71 x 36) and Relief: Solar Projectile (36 x 71)] were all made in welded steel.

Taylor's daughter Melanie recalls how, at his Towednack studio, her father was able to cast small bronzes using the lost wax process, as well as weld.

|

| The Studio at Towednack (May 2014) |

Young artists who produced large bronze pieces, like Denis Mitchell's Turning Form, needed either the support of a sponsor, in Mitchell's case Ben Nicholson, or a public commission like those instigated by the Festival of Britain.

In the case of Chadwick, a commission from the Festival of Britain, selection for the 1952 Venice Biennale, and being awarded the International Prize for Sculpture at the Venice Biennale, in 1956, and a firm contract with Wadington's enabled him to work on a larger scale in welded steel and bronze.

The series of exhibitions Sculpture in the Home, sponsored by the Arts Council (1946-59), would have provided an ideal context for Taylor's work; but his work seems to have escaped the attention of the selectors.

[See the exhibition: The Sculpture in the Home Exhibitions, The Henry Moore Foundation]

FROM ORGANIC TO MINERAL

Representing an ultimate stage in distilled organic forms — perhaps informed by the spirit of vitalism — the work below is evocative of the naturally-shaped rocks collected in China, as objects of contemplation, and valued on a par with works of art, and in some cases, even more, since the 17th century.

[See the exhibition: Objects of Contemplation: Natural Sculptures from the Qing dynsaty, Henry More Institute 12 Dec. 2009 - 7 March 2010].

Here, the form displays a hybrid naturalness that blurs the boundaries between organic and mineral and transcends the arbitrary divide between figurative and abstract:

Transcending categories, Taylor's sculpture seems to realize Stan Geist's idea of 'a figuration with a presence', and with what Elaine de Kooning called the 'equally real visual phenomena of the world around us'.

Stylistically, we are far from the highly polished forms developed by Hepworth; emulated by his friend Roger Leigh and Denis Mitchell; and far also from the rigorous geometric abstractions of Brian Wall, with whom Taylor regularly exhibited at the Penwith Gallery.

Defining a path between neo-classical figuration and geometric abstraction, Taylor defined his own path along the lines of a secular Vitalism, and produced works deeply rooted in the organic world; even if, at times, the reference to nature seems tenuous.

Like the Lingbi meditative rocks of China, the modest scale of these works was not intended to stand out in open air exhibitions, or fight other works in public spaces, but were suitable for display in domestic settings — 'chamber works', that would have been at ease in Jim Ede's home at Kettle's Yard.

A photograph of an other version of the same sculpture:

taken from a slightly different angle, shows that what first appeared to be a rock (abstract mineral form) gradually emerges as a vestige of an organic life form: a 'trans-human' rendering of the human body: reconfigured as a tense, living mass of energy, balanced in space; like a dancer poised in a precarious state of equilibrium, challenging gravity; beyond Rodin, Degas, Matisse and De Kooning.

PAINTINGS AND DRAWINGS AS A LABORATORY FOR EXPLORING SCULPTURAL FORMS

Ore stream', (oil on masonite, 1957), shown in 1958 at the Drian Gallery, is the earliest two-dimensional work in the exhibition. There may be a reference to mining, here; and this work may also relate to Landscape 1957 (also exhibited at Drian); however the reference seems more symbolic than naturalistic. The composition suggests a three- dimensional space into which an symbolic abstract event is unfolding, in the dynamic movements of lines that, for me, evoked blood and fire or the symbols of the Crucifixion:

This painting, an oil on board, is set in a rudimentary box frame (made by the artist, with cheap material); painted white, and now bearing the marks forty eight years of sun, dust, handling and storage…

The mounting and framing, in its raw ('Arte Povera') materiality has become an intrinsic part of the work, and gives the painting a three-dimensional quality, appropriate to its subject: energy unfolding in space.

Contrasting with the smooth surface of the painting, the frame suggests a rough, deliberately non-precious approach.

Beyond the reference to mines and mining, the interpretation of the subject and the title of the picture, 'Ore stream', suggests a flow of energy moving through space…Iconographically it evokes a sacrificial space and, within it, an open totemic structure in perpetual mouvement. It may also connote a scene of the Passion after the body has been taken away and the crowds have departed.

The ink drawing reproduced on the cover of Taylor's 1958 Drian solo exhibition catalogue may be 'Drawing for sculpture' (Drian cat. nº8), and bears strong similarities in its structure and its dynamism of forms:

|

'Drawing for sculpture', August 1957 (?) |

By suggesting materiality through lines of energy, both painting and drawings seems to confirm Taylor's view that 'The space created between and displaced by the form is more important than the form'.

Both painting and drawing bear strong formal similarity with the sculpture May-bug, (Drian cat. nº 8) for which they may have been prelimirary studies.

In what is very likely one of his 'Drawing for sculpture' (dated 1959),

Drawing for sculpture, brush and Indian ink on paper, 1959

|

Taylor's drawing, however, is not a pastiche and the variety of its brush strokes and washes, and their dynamic articulation in space — along vertical, horizontal and diagonal axes — may also allude to and project the action of the oxy-acetylene cutter onto sheet metal; as an anonymous note about his sculpture 'May-bug', pencilled in the catalogue of his Drian solo show suggests: 'sheet metal torn apart by oxy-acetelene cutter. Spiky shapes'.

|

| 'May-Bug'. 1957-8. |

The drawing, however, stands in its own right, as an expression of vitalist energy.

A PARADIGM SHIFT (sans lendemain)

At this point, where the dualism figuration-abstraction seems to dissolve, Taylor produced a remarkable photomontage consisting of a black 'abstract' painting on film, which he set on a window pane, then photographed it against a background of roof-tops; probably from the second floor of his studio at 36 Fore Street.

The effect is striking and highlights Taylor's free engagement with and reconciliation of the two main strands (figuration and abstraction) that polarised the artistic community in St Ives, and caused tensions and enmities throughout the period he remained there:

The result is striking; but may be a one-off, for we don't know whether Taylor made other similar works. In any case it has paradigmatic value and defined the basis for a practice that would combine photography and painting with the mediation of installation.

It is clear, however, that Taylor would never have been able to exhibit this piece in St Ives when it was made; for, in spite of many precedents in Europe of artist using photography experimentally, and, recently, the experiments with collage by Edoardo Paolozzi, Nigel Henderson and the Smithsons, photography as a medium was not accepted as a fine art medium. There were no photographers, for instance, among the members of the Penwith Society.

When photography attempted to be 'art', as seen in the touring exhibitions organized by the C.S. Association, it was 'as a means of expression reflecting contemporary life', and by 'breaking away from the conventionally "pictorial"'; but still working 'on the assumption that 'photography is representational, familiar' [CS Exhibition 1955-57].

For Roger Mayne, taking and exhibiting a picture of roof tops (similar to the one seen in the background, here; only more panoramic, was about the limit of a permissible subject-matter for a photographer with artistic ambitions.

In St Ives and elsewhere artists called upon photographers like Roger Mayne to document their work or take their portrait in their studio, but did not consider that they could have used their camera for making art on an equal artistic footing with painters and sculptors.

Whereas some artists like Peter Lanyon took photographs to gather material for their paintings (as an extension of sketching), Taylor, in this paradigm-shifting work, broke new ground by creating an extra-ordinary, 'one-off' piece: an 'idiolect' that stands out, to this day, in the history of St Ives art, and in the history of British Modernism, by the radical paradigm shift it proposed.

For more information on Henry Moore visit Artsy's Henry Moore page (https://www.artsy.net/artist/henry-moore). Our Henry Moore page provides visitors with Moore's bio, over 200 of his works, exclusive articles, and up-to-date Moore exhibition listings. The page also includes related artists and categories, allowing viewers to discover art beyond our Moore page.

ReplyDelete